I knew you

Tried to change the ending

Peter losing Wendy, I

I knew you

Leavin’ like a father

Running like water, I

And when you are young, they assume you know nothing.

When Swift’s speaker sings in ‘cardigan’ that the object of the song ‘tried to change the ending, Peter losing Wendy’, she encourages us to go back and take a closer look at a story that may have been a staple of our childhoods.

The line is deeply ambiguous, and has always puzzled me. It’s unclear whether he tried to change the (happy) ending, making it so that Peter instead lost Wendy; whether he tried and failed to change the (unhappy) ending of Peter losing Wendy; whether he tried to change the (unhappy) ending, but Peter lost Wendy anyway. Is Peter losing Wendy the result of his actions, or the fate he tried to change?

Regardless – or perhaps because of – this ambiguity, the line might prompt us to go back to J.M. Barrie’s 1911 novel Peter and Wendy. The story has been so repeated and romanticised over the years that its ending is perhaps not commonly known – a good example of what Linda Hutcheon calls a ‘generally circulated cultural memory’, of a text or work of art that we think we know because of how pervasive it is in popular culture, but which we might never have encountered directly.

The generally circulated cultural memory of Peter Pan is predominantly shaped by Disney’s 1953 film, Peter Pan. It ends with Wendy telling her parents excitedly about her adventures in Neverland. At the end of Barrie’s novel, however, Peter promises to return to Wendy every year and take her to Neverland for spring-cleaning time. She waits patiently in a brand new dress, but he never comes. I can’t help but think of Swift’s ‘All Too Well (10 Minute Version)’ and ‘The Moment I Knew’. She watched the front door all night, willing him to come; she sat there in her party dress, with red lipstick but no one to impress.

Years later, Peter finally returns and finds Wendy a married woman, with Peter ‘no more to her than a little dust in the box in which she had kept her toys’. He is shocked and furious that she has dared to grow up. She feels something inside herself crying, ‘Woman, woman, let go of me’. The image of Wendy’s inner child screaming to get out haunts me.

Peter sobs, Wendy comforts him, and then she allows her daughter, Jane, to fly to Neverland with him for spring-cleaning time. The cycle continues as Jane grows up and lets her own daughter, Margaret, fly with Peter, ‘every spring-cleaning time, except when he forgets’ (ouch). This will continue indefinitely, Barrie’s narrator tells us, ‘so long as children are gay and innocent and heartless’.

It’s a little jarring to end a children’s novel with the assertion that children are heartless. But laced through Barrie’s Peter and Wendy is a surprising amount of vitriol directed at both adults and children. It’s certainly an interesting choice for a children’s classic, and it’s no surprise that Disney left out a lot of its complexity (while unfortunately retaining its racism), making the Peter-Wendy relationship into more of a straightforward youthful romance.

In Swift’s hands, though, we get some of that complexity back. She’s certainly moved on from idealising ‘never growing up’, as she did on Speak Now. Coupled with the line ‘leaving like a father, running like water’, and heard in the context of the Betty-James-Augustine love triangle (we know the object of the ‘cardigan’ has cheated on the speaker), the reference to Peter losing Wendy reframes Peter and Wendy as the story of a thoughtless, selfish man-child who refuses to grow up and take responsibility. It’s the same story, in fact, that lies behind the coining of ‘Peter Pan syndrome’ in popular psychology, to refer to individuals – often exhibiting similar traits to narcissistic personality disorder – that refuse to grow up.

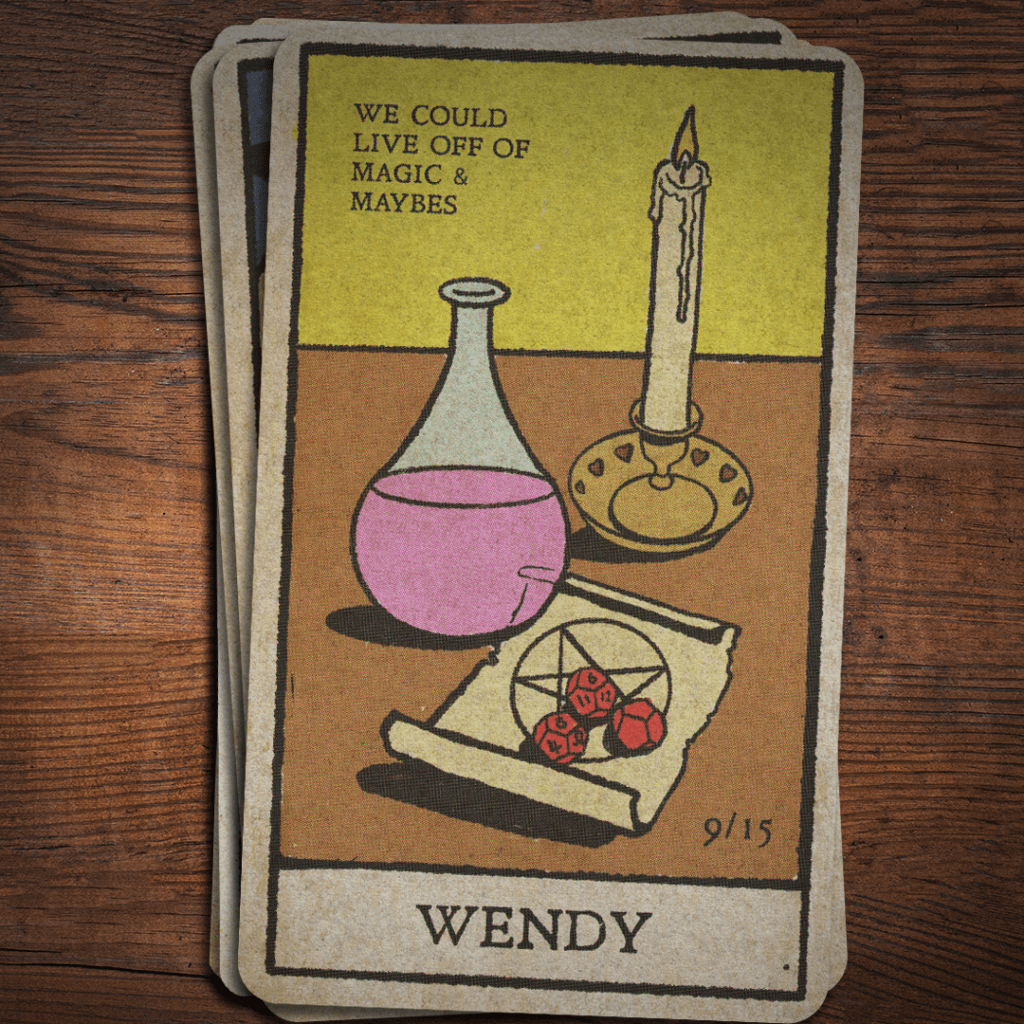

Swift isn’t the only woman rethinking the story of Peter Pan for the (feminist) twenty-first century. British singer-songwriter Maisie Peters, in her 2023 song ‘Wendy’ (from album The Good Witch), goes even further than Swift’s ‘cardigan’. She explicitly associates Peter Pan syndrome with deeply flawed and potentially abusive gender dynamics. In the chorus, Peters sings to a lover, ‘you could take me to Neverland, baby/We could live off of magic and maybes’. But the speaker knows this romantic idea isn’t realistic. She realises that ‘Behind every lost boy, there’s always a Wendy’ – one who will take on the emotional labour of trying to keep him on the straight and narrow, until he gets bored and wanders off to the forest. In doing so, she will lose the chance to achieve her own dreams:

Take the hand and go with him

Be the clock that he watches

Wait until he gets bored and

Wanders back to the forest

Lose the world that you live in

Pretend that it’s what you wanted

It’s a life I could have, I know.

The speaker of the song can see this future clearly, and tells us it scares her: ‘if I’m not careful, I’ll wake up and we’ll be married, and I’ll still flinch at the sound of a door’. It gets old being forever 20,’ she admits – and it’s unclear whether she’s talking about herself, or her reaction to his refusal to grow up.

The key lines, for me, come early in the song: ‘Lost my page when you kissed me, now I remember the whole book – she almost loses her way ’cause she followed him after one look’. What woman hasn’t found herself so caught up in love, and fairytale-inspired dreams of romance, that she lets herself dissolve into an unequal partnership?

Peters has, though, remembered the whole book – and she’s urging us to remember it too. We need to look past the vague notions of romance and adventure we might remember from our childhood, and dig a little deeper into the dynamics of Barrie’s creation – and its problematic legacy. ‘Wendy’ is an updated Peter Pan for a feminist generation cognisant of concepts like weaponised incompetence and the mental load.

The Wendy of Peters’s song makes a decision: ‘so I’ll lock the window and turn on the AC/You’ll throw your rocks and you’ll scream that you hate me’. Peter Pan enters by the window in both Barrie’s novel and Disney’s film, so this is a deliberate choice to turn her back on him and everything he represents. It’s the very same sentiment we get at the end of Swift’s ‘Peter’, from The Tortured Poets Department. After waiting, repeatedly, for him to grow up and come and find her, as he promised, she finally gives up:

And I won’t confess that I waited

But I let the lamp burn

As the men masqueraded

I hoped you’d return

With your feet on the ground

Tell me all that you’d learned

Cause love’s never lost when perspective is earned

And you said you’d come and get me but you were 25

And the shelf life of those fantasies has expired

Lost to the lost boys chapter of your life

Forgive me Peter, please know that I tried

To hold onto the days when you were mine

But the woman who sits by the window has turned out the light.

‘Lost to the lost boys chapter’ of his life, the Peter of Swift’s song could be the very same man as in Maisie Peters’s song, wandering off to the forest and leaving Wendy in perpetual anticipation and, ultimately, crushing disappointment.

Both speakers refuse to let this become their fate. Swift’s turns off the light – though I would actually argue that she turns on the light. She brings the idealised dynamics of Barrie’s beloved classic into the harsh light of day, where they don’t stand up to scrutiny so well. Peters’s song ends with the lingering and, I think, defiant question, ‘What about my wings? What about Wendy?’

What about Wendy, indeed? After all, Barrie’s novel was called Peter and Wendy, but these days we refer to it only as Peter Pan. Thanks to artists like Peters and Swift, though, the resurrected Wendy is having something of a moment. It’s a moment that shows the power and importance of adaptation.

Adaptation can be both an homage to a previous text or work of art, and an act of intense interrogation. Adaptations don’t just descend passively from originals like an apple falling from the tree – they exist in dialogue with them. Peter and Wendy, and Swift’s and Peters’s songs, mutually enrich each other. They enable us to know, and to question, both the new narrative and its original. We can enjoy nostalgia for a childhood classic, while, as adults, awakening to some of its more poignant, even concerning, subtexts.

Swift and Peters point out the problems of trying to live by the outdated gender roles of fairytales and children’s books – something Swift also explored as early as ‘White Horse’ – and the tendency of older literature to reinforce problematic patriarchal ideologies that adversely impact women’s wellbeing. It’s time to stop tolerating men who refuse to grow up – it’s not cute, impish or charming, and it’s a luxury most men can only afford because their adult needs and responsibilities are taken care of by invisible women – women who, conversely, probably had to grow up too soon. Does the fairytale save the damsel in distress, or might it actually create more distress for that damsel in the long term?

Johannes Fehrle points out that perceptions of ‘original’ texts are inevitably influenced by later adaptations, so we can never in fact return to a pure original. And perhaps, in the case of Peter and Wendy, that is a good thing. It’s a good example of a story that shouldn’t be relegated to Neverland and permitted to ‘never grow up.’ On the contrary, it’s one of many stories we need to keep returning to and interrogating in the twenty-first century.

We need to keep asking: what about Wendy?

Hello, I love it ! I didn’t know Maisie Peter’s Wendy.

I think it’s also interresting to understand Swit’s songs order for her last album. Personnaly, I link her Peter to songs before and after.

The way I see it, we are in the “tales’ part” of the album starting with I Look In People’s Windows. The song is about longing to know how the person she wishes to see is doing and waiting for some news while also searching for it (so not really the ‘stasis’ you refered to for Right Where You Left me in an other post). Next one is The Prophecy with a sense of doom, she feels cursed, maybe it is a sentence (‘was it punishment?’) or its some kind of a dumb mistake (‘fools in a fable’) ? Still, she tries to change her ending of loneliness, letting go of pride and begging for love to come her way. This one is followed by Cassandra which is about… a prophecy and a curse. And how no one believed her and the loneliness of being let down. Nevermind, she tells her story either way. She won’t wait for someone to rescue her or to write her story for her (without her). She choses what she will do with her life (even if people don’t want to listen to it or criticize her for it). And that’s what we find in Peter also. She has tried to be there for him when he’d come back but she chose her path without really waiting. It was more about hope than wait ( ‘I won’t confess that I waited’ + ‘I hoped you’d return’). The Bolter follows with the idea that this girl is jumping from one love to another, from one story to another. It’s funny and a bit dramatic, she doesn’t wait for things to turn bad, she leaves at the first sign of danger and they get mad at her for it. (This reminds me of Maisie Peters ‘you’ll throw your rocks and scream that you hate me’ in Wendy) But she’s free, relieved of the weight of him (I want to say the wait for him ?) and happy. Which turns into Robin, a child living carefree of social norms and the beauty of it. Society judges Cassandra for speaking the truth, judges women who wait too long (ie. celibacy, childless) but also the ones who don’t wait enough (understanding : sacrifice their lives for men), jugdes the Bolter girl for living by her own rules. So, Robin, enjoy your freedom and the absence of contradictions imposed on women while you’re a kid. It’s almost some kind of promise from Swift to try to protect that kid from knowing patriarcal’s expectations because she learned you can never succeed (Lizzie Bennet’d say ‘Such a woman doesn’t exist.’) so don’t play by anyone’s else rules and don’t wait for a man, you should put yourself first.

I also finding interresting to see how her songs begin and end, fading into one another :

1) ‘I had died the tiniest dead’ – ‘What if your eyes looked up and met mine one more time’ (She hopes to catch something that will change the course of their actions.) >

2) ‘Hand on the throttle, taught I had catch lightning in a bottle. Oh but it’s gone again’ (Maybe his glance ?) – ‘I look to the sky and said Please’ (She dreams of a new love through wondering why she is the way she is.) >

3) ‘I was in my new house placing daydreams ‘ – ‘When the turths comes out it’s quiet, it’s so quiet’ (Cassandra was killed for telling the truth because of a curse and Swift felt abandonned.) >

4) ‘Forgive me Peter, my lost fearless leader’ (‘Forgive me Peter’ like a prayer) – ‘Words from the mouths of babes, promises ocean’s deep but never to keep’ (Hoping he’ll chose to grow up so they can be together.) >

5) ‘By all account she almost drown whe she was six in frigid water’ (Was it the ocean’s deep water ? Six y.o. as words from the mouths of babes ?) – ‘And she realised it felt like the time she fell through the ice and came out alive’ (Feeling free, from promises and from anyone’s expectations.) >

6) ‘Long may you reign, you’re an animal. You are bloodthirsty’ – ‘… wilder and lighter for you’ (A song about a kid who lives freely, surrounded and protected for now and how precious it is.).

I’m not saying it’s what she intended from the start (I doubt it) but it reads like a story with characters learning from previous ones. Or maybe they’re the same person remembering past-selves (‘all her f*cking lives flashed before her eyes’), honoring where they came from and who they are ?