With less than 24 hours to go before perhaps the biggest release in music history – Taylor Swift’s hotly-anticipated eleventh album, The Tortured Poets Department, already downloaded over 200 million times after being leaked the day before the official launch – the requests have started to roll into my inbox from journalists, all asking a variation on the same question: does this mean that Taylor Swift is, like…a poet? An actual…poet?

I can understand where this comes from. With the album’s black-and-white, folklore– and evermore-esque aesthetic, its highly self-aware literary references (‘The Manuscript’; ‘The Albatross’; ‘veins of pitch black ink’; the possible allusion to Dead Poets Society), its complex vocabulary and its promotional gold bookmarks, Taylor certainly seems to be courting the kind of reception and discussion that academics have been engaging in for a while now. Such discussion recognises Taylor as writing and performing within traditions established by, among others, the Romantic poets and Emily Dickinson, and acknowledges the multiple literary references within her work. Yet it seems to have taken Taylor’s explicit use of the word ‘poet’ in her new album title, along with her adoption of the moniker ‘Chairman of the Tortured Poets Department’, to prompt this new, specific line of enquiry: is Taylor a poet? Not just someone who drops the odd reference to Romeo and Juliet or Jane Eyre, but – a poet?

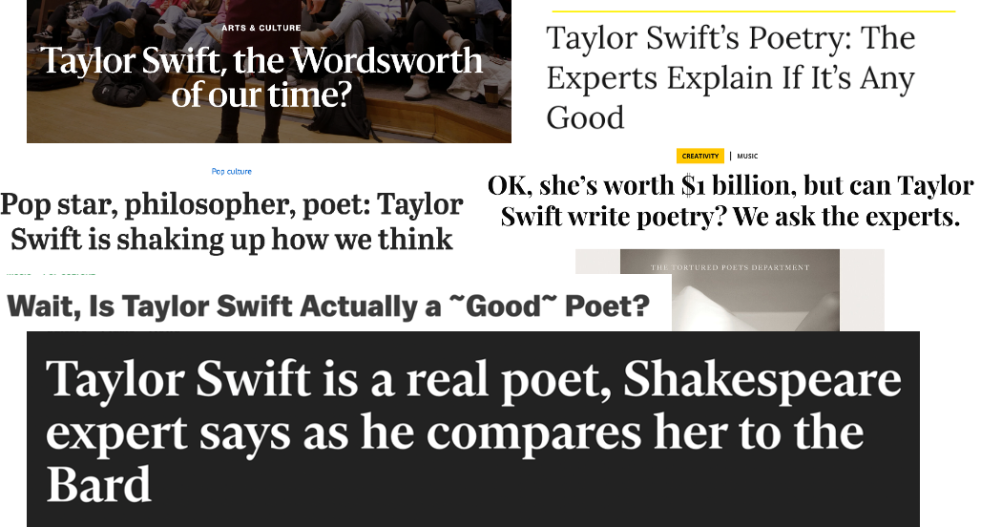

It’s the new ‘is Taylor Swift the new Shakespeare?’ which, let me tell you, guys, is now soooooo 2023. Who’s ‘is Taylor the new Shakespeare’ anyway? Ew.

Just as the question ‘is Taylor Swift a poet?’ echoes the ‘is Taylor Swift literature?’ or ‘is Taylor the new Shakespeare?’ questions, so my response now echoes my former response to those. Succinctly, it’s this: you’re asking the wrong question(s).

Perhaps instead, we should ask why it’s newsworthy at all to suggest that Taylor Swift might be a poet. I had to disappoint one journalist with the news that he wasn’t the first person to ask me that question, which suggests to me that there are reporters out there who genuinely think this might be a radical take. Let’s unpack that for a second. It’s radical to suggest that a young woman writing about her feelings, her dreams, her disappointments; about glitter, red wine, bare feet, salt air; a woman who packages those moments and snapshots up in surprising and delightful metaphor and lingering imagery – is a poet? Dude, have you read any poetry?

Which leads us to this question: since her lyrics tick a huge number of the boxes of things we might typically associate with poetry (rhyme, figurative language, emotion) what’s stopping you, then, from thinking that Taylor’s work is poetry?

Is it the fact that it’s set to music, and tends to be consumed aurally rather than visually, and performed rather than remaining confined to the typed (or handwritten) page (or album liner notes)? If so, that shows an interesting evolution on poetry’s part. After all, poetry was originally an oral form, often set to music, performed by masters of the craft who would learn hundreds, sometimes thousands, of lines off by heart (hence the alliterative metre of Old English poetry, which helped jog the memory of its performers). The love poetry of sonneteers like Thomas Wyatt and Philip Sidney would have been recited at the Tudor court to select coteries of friends and acquaintances. That somewhere down the line poetry shifted to the page, from the public to the private realm, simply showcases its versatility, but certainly doesn’t preclude words set to music from qualifying. If anything, it’s perhaps a sad indicator of how distanced we’ve become from the potential of poetry, with school curricula tending to focus on ‘canonical’ works read from the page, overlooking other more dynamic and exciting forms like spoken word, slam, and beat poetry. There’s a classist and potentially racist issue here, too, with curricula tending to prioritise the same very narrow selections of canonical poets, who are mostly, if not entirely, white and upper- or upper-middle class.

Or – just as troublingly – is it the fact that this ‘poet’ is a charming blonde woman who makes no apology for her girlishness, her quirks, her very feelingy feelings; a woman whom many people still believe reached the epitome (or should that be nadir) of her lyrical talent with ’cause the players gonna play play play play play and the haters gonna hate hate hate hate hate baby’? Could it be that we’ve been fed a bunch of sexist, elitist nonsense through the media and our education systems which still has us believe that ‘poet’ refers to a white man – probably British, definitely dead by 35, almost certainly wearing a ruff – from the sixteenth century?

I’m almost certainly overthinking some of this, of course – occupational hazard, it’s literally my job. Anything Taylor obviously makes a clickable headline. But sometimes I think it’s worth pausing to reflect on the questions that coalesce and circulate around her music, and to ask one back: why are we asking those questions? What assumptions have led us to that line of questioning, and might they have problematic underpinnings? In this case, they’re potentially founded on a problematic combination of elitism, sexism, and a generation raised on biased, narrow school curricula. Perhaps it’s time to start asking yourself: why wouldn’t Taylor Swift be a poet?

Professor McCausland-

Inspired in part by your last two posts and earlier “Taylor Swift and the Death of the Author” post, I’ve written this treatise (??) on “So High School.” I hope you enjoy it!

Ethan Melone Seattle, Washington USA

A Treatise on “So High School:” Being an Attempt to Demonstrate its Status as the Greatest Love Song Ever Written So High School T. Swift Let’s start with the title and the first double-meaning in the song. When someone says “that’s so high school,” it is pejorative, it roughly translates to “so immature,” often representing overt attempts to increase social status. From a biographical (extra-textual) perspective—always a consideration in Taylor’s work—it reflects the initial public consensus on her relationship with Travis Kelce. But the second meaning is: you make me feel innocent again. (One might not always associate high school with innocence, but this is reinforced by lines 22 and 26 as discussed further below.) Here we have to consider the intertextuality of Taylor’s work, both within her own catalogue and to other works and cultural references. Taylor has written many songs about her lost/stolen innocence, notably “Dear John,” “Woud’ve Could’ve Should’ve,” “The Manuscript.” She also traces this professionally to the beginning of her career, while in high school, in songs including “Who’s Afraid of Little Old Me” and her commentary on “Clara Bow.” Now, she feels “so high school” again: her stolen innocence has been returned to her by this new love. 1. I feel so high school every time I look at you 2. I wanna find you in a crowd just to hide from you The first line is a simple preamble/declaration, akin to “Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day” or “How do I love thee? Let me count the ways.” 3. And in a blink of a crinkling eye (AA’B) 4. I’m sinking, our fingers entwined (AB’) 5. Cheeks pink in the twinkling lights (AA’B’) 6. Tell me ’bout the first time you saw me (C)

Taylor sings this stanza at a higher pitch the second time through, conveying increasing emotion.