‘Too many young women yearn for annihilation’, reads the clickbaity subtitle of Mary Harrington’s article ‘The Dark Truth about Taylor Swift’. Published on 16 August 2023, Harrington’s piece observes a troubling tendency in young women towards ‘a craving for romantic transcendence that’s difficult to distinguish from self-destruction’: in other words, an obsession with, and yearning for, love affairs made all the more intense by the knowledge that they are doomed to failure (such as Jack and Rose from Titanic, or Romeo and Juliet). Harrington attributes some of Swift’s popularity to the fact that her oeuvre satisfies this desire: her best songs are about romantic liaisons that don’t end well (‘got a history of stories ending sadly’). Harrington then goes on to link this to thirteenth-century France and the massacre of the Cathar sect of Christianity, who saw our incarnated world as fundamentally evil and longed to escape the ‘prison’ of flesh to return to unity with God. Following their persecution during the Albigensian Crusade, the Cathars’ beliefs went underground and spawned what we now know as ‘courtly love’ literature.

For courtly love in the English literary context, think Geoffrey Chaucer’s Troilus and Criseyde or The Knight’s Tale; the Arthurian legends; Sir Gawain and the Green Knight; early iterations of the English sonnet (such as Philip Sidney’s Astrophil and Stella, or Sir Thomas Wyatt’s ‘Whoso List to Hunt’) and certain plotlines from Shakespeare. Common to these is the trope of unrequited love between a man and the (married) lady he idolises. He places her on a figurative pedestal, sending her love letters and spending a lot of time weeping and wishing he was dead, such is the pain of his unreciprocated passion. If, Harrington argues,

as it was for the Cathars, every soul was trapped in a state of longing for reunion with the Divine, when the troubadours sang of unrequited love of a knight for his ‘Lady’, that wasn’t a literal love story. On the contrary: it stood for that spiritual pain and longing. And because such a longing could only be attained by escape from the prison of flesh — which is to say, by death — the love of a knight for his ‘Lady’ could not be consummated, except by the death of one or both. In other words: […] the narrative ‘romance’ couldn’t have a ‘happy ever after’ […] the only real happy ending is death.

In an increasingly secular world, ‘what began as an esoteric way of describing the yearning to leave flesh behind and reunite with the divine becomes, in a world with no divine, something more like a longing for passionate self-annihilation.’ Harrington then, somewhat bafflingly, segues straight from Swift’s lyrics in ‘Willow’ (‘I’m begging for you to take my hand, wreck my plans, that’s my man’) into the apparent popularity, among young women, of ‘breath play’, or choking during sex: ‘I suspect the practice is a by-product of the same buried hankering after passion-as-annihilation […] if the only transcendent desire is one that ends in death, the closer sex comes to that threshold, the nobler and more intense it is.’

She ends by contending that although Swift’s work ostensibly ‘recounts relatable romantic highs and lows’, it is in fact underpinned by the 800-year-old glorification of whose who seek a union with the divine in death: the young women who ‘thrill to this promise […] don’t even realise that what they crave is not sexual, or romantic, or spiritual’.

It’s a lot, right? On a Wednesday morning, drinking tea and scrolling through an article your colleague sent you on Facebook, to suddenly discover that you’re probably into strangulation during sex and have actually been harbouring a deep-seated yearning for total union with the divine beyond the torturous incarnation of your corporeal prison. And you just thought you liked Swift’s sick beats.

For the record, I think Harrington’s article makes some interesting points, and perhaps the links and connections she identifies are no more tenuous than those I have flagged up in previous posts on Swifterature.com. What really struck me, though, is the anxiety it expresses about the tendencies that popular culture might cultivate or unleash in young women.

I can’t help but recall George Eliot’s ‘Silly Novels by Lady Novelists’, a satirical essay published anonymously by the Westminster Review in 1856. In this, Eliot refers to the eponymous silly novel as ‘a genus with many species, determined by the particular quality of silliness that predominates in them’. She goes on to outline a typical such novel: the heroine is ‘usually an heiress’, with dazzling wit and beauty, and ‘a crowd of undefined adorers’ constantly pursuing her. Even when put through dramatic trials – she ‘as often as not marries the wrong person to begin with, and she suffers terribly from the plots and intrigues of the vicious baronet’ – she ‘comes out of them all with a complexion more blooming and locks more redundant [abundant] than ever’. In short, as twenty-first-century fanfiction or creative writing aficionados will recognise, the protagonist of these silly novels is the Mary Sue – an authorial self-insertion that is usually the product of authorial wish-fulfilment. With her dramatic romantic life, dazzling beauty and wealth, nose and morals ‘alike free from any tendency to irregularity’, and ‘superb contralto and a superb intellect’, she might also be a character from a Taylor Swift song (‘Dorothea’, ‘When Emma Falls in Love’ and ‘The Last Great American Dynasty’ spring to mind). She might, indeed, be Taylor Swift herself.

The real damage done by these novels, Eliot laments, is that they ‘confirm the popular prejudice against the more solid education of women’. If this is what literate women produce, society might say, then best keep them away from an education. She didn’t say it directly, but Eliot implies that these silly novels are undoing all the good work of pioneering feminist Mary Wollstonecraft, who argued in ‘A Vindication of the Rights of Woman’ (1792) for female education. Wollstonecraft posited, persuasively and in elaborate rhetorical style, that education for women could only benefit society, as it would produce substantial, interesting women whose company men might actually find intellectually stimulating (imagine that!) and who were fit to be more than simpering drawing-room ornaments.

Let us turn to another progressive literary woman. Jane Austen wrote her now-classic novels when the very idea of a silly novel by a lady novelist was still something of a nascent phenomenon. No doubt taking a close personal interest in the eighteenth-century reception of female-authored novels, Austen mounts an affectionate defence of them in her first full novel (but last published work) Northanger Abbey (1817). It is no coincidence that this work came into being during the period where the novel was increasingly identified as a woman’s form (by the end of the eighteenth century, half of novels published were penned by women). Austen seems to anticipate Eliot’s critique, decades prior: the heroine of her novel, Catherine Morland, is decided un-heroic, and certainly not a Mary Sue. She has enjoyed a drama-free upbringing, is ‘almost pretty’, has no perceptible talents and is generally a nice, unremarkable girl. As she transitions into society, Catherine is surrounded by voices telling her what she should and should not read.

It is again no coincidence that one of the novel’s silliest (female) characters, Isabella Thorpe, is an avid reader of novels by woman authors – Gothic novels such as Anne Radcliffe’s The Mysteries of Udolpho (1794) in particular. The plot of Northanger Abbey hinges upon Catherine’s brains having been so addled by such novels that, in an awkward moment, she insinuates that her prospective father-in-law murdered his wife. Henry Tilney, son of said father, and Catherine’s love interest, is (understandably) disappointed and dismayed:

‘If I understand you rightly, you had formed a surmise of such horror as I have hardly words to —- Dear Miss Morland, consider the dreadful nature of the suspicions you have entertained. What have you been judging from? […] Dear Miss Morland, what ideas have you been admitting?’

Perhaps Austen was thinking of this 1784 poem, ‘O Leave Novels’, by Robert Burns:

O leave novels, ye Mauchline belles,

Ye’re safer at your spinning-wheel;

Such witching books are baited hooks.

No matter that Catherine is ultimately partially correct about General Tilney – who turns out to be a thoroughly horrible man, although not guilty of uxoricide – Northanger Abbey does indeed suggest that too much uncritical reading might be dangerous to the female sensibility.

As scholar Margaret Beetham points out, women have historically been perceived as prone to ‘inappropriate reading’: that is, they might ‘misidentify with female heroines or take for fact what should be understood as fiction’, and since they are ‘likely to be governed by feeling rather than intellect’, they are, apparently, particularly susceptible to novels of high emotion. It’s not a huge jump from this to Harrington’s assertion that female fans of Swift’s music and lyrics are confusing the reality of romantic love with the fantasy of total spiritual annihilation.

Overwhelmingly female, the Swiftie community have received damning media attention for their pack-like mentality and tendency to overwhelm or persecute anyone they feel has threatened the wellbeing of their idol. Just recently, they managed to manipulate the results of the prestigious ‘Golden Boy’ football award by vigorously supporting the opponent of a candidate who had publicly voiced his dislike of Swift’s music. Their anticipated rushing of ‘Eras Tour’ cinema screenings resulted in the forced rescheduling of the Exorcist reboot (which is an interesting twist, considering my comparison of Swift with the Gothic genre in this piece). I myself have deployed the word ‘rabid’ to describe this phenomenon on multiple occasions, consciously distancing myself from ‘that type’ of Swiftie; the kind whose behaviour male TikTok creators have deemed deserving of a ‘red flag’. Feminist media scholar Melissa A. Click has noted the disparity in representations of ‘fanboys’ versus ‘fangirls’, the former attracting more respect, with the latter often diminished and ridiculed (indeed, to ‘fangirl’ over something is shorthand for behaving embarrassingly and emotionally).

The ways in which women select and consume culture has always been problematic within patriarchal society. In The Woman Reader (1993), Kate Flint argues that “the debate about what women should, and should not read, and how they read, was not a new one, nor has it disappeared”. A couple of years ago, a former student of mine wrote her Masters thesis on similarities between Northanger Abbey, the reception of eighteenth-century Gothic novels, and Stephanie Meyer’s Twilight series. In all cases, what initially seemed to be simple snobbery revealed itself as more specific and targeted: anxieties regarding these new cultural forms tended to coalesce exclusively around young women, and what such forms might do to their apparently fragile intellects and emotions. The act of reading itself has even been discursively used to confirm women’s inherent weakness, since fiction was historically seen as a soft option.

I hear echoes of this in the negative reactions to my Taylor Swift university course, which imply that this is not a worthy object of study. I hear it in the numerous emails I’ve had from young women who tell me their professors discouraged them from writing about Swift for their bachelor or Masters’ theses because – I’m paraphrasing – ‘she only writes about boys and breakups’. Disregarding, for a moment, the fact that if we excluded such themes from the literary canon then we would have no canon left, there is again something peculiarly misogynist in this critique. It’s the same note I hear in criticism of Swift’s ‘girlishness’, an assertion that assigns women writing about heartbreak a shamefully childish edge; we really should have known better and learned to control our emotions, like grown-ups. When The Beatles wrote ‘Yesterday’, I guess they must have been writing about a more respectable, manful, adult anguish.

It’s the same note struck in Anne Helen Petersen’s observation of reader responses to the Twilight series: that ‘adult readers are ashamed of reading in a style usually associated with young girls’ – as if the heightened emotion and passion that saturates the Twilight saga should have been locked away and neatly bracketed off within our adolescence, not permitted to spill out into the more refined contours of adulthood. It brings to mind the medieval notion of women as embarrassingly leaky vessels, whose messy emotions the weary, noble patriarchy is perpetually tasked with keeping in check.

Women just cannot be trusted with culture, is the implication. We take it too far, we become obsessive. We become emotional. Our emotion infantilises us, sends us back into the realm of childhood where fantasy and reality were indistinguishable from one another, and sends us on dangerous paths towards risky sex and doomed romance.

Or, to put it another way: whatever popular culture you choose to consume, ladies (and all who identify as such), it will inevitably diminish you in the eyes of the patriarchy and fill your head with dangerous ideas. If that isn’t good grounds to keep going, I don’t know what is.

My thanks to former student Nora for first getting me thinking about this.

Every time there’s a conversation about women’s representations in literature, I think of Persuasion (Jane Austen) : when Captain Harvile asks Anne Elliot if books might be used as a proof of female fickleness and she answers no, because books are written by men. (I think of it as an addition to the idea of women readers she wrote about in her early years with Northanger Abbey.) But, in this article, a lot of your examples are written by women, some of them warning us about the danger of believing every word you read and the others, well, proving that danger. About the first one, Swift has done it with Dear Reader. And about the latter, I’m wondering a few things… I believe that feminism isn’t about having the same power as men or to reach the same spheres but to break (free from) patriarchy. So why would women writers want to write using same rules than men (the ones depicted in “Silly Novels by Lady Novelists” are a perfect example) ?

But at the same time, why could women not use these stereotypical traits and scenarios to have fun with them and sometimes, like with Jane Austen, to criticize them ? From Northanger Abbey, to Persuasion, I’m also thinking about Emma or Lizzie Bennett talking about refusing a marriage proposal while everyone think women should accept them no matter what because their lives revolve around it. Something Swift addresses too in Lavender Haze, Champagne Problems and (the prologue of her) Bejeweled music video. Or, like your reference to Wollstonecraft about women being ‘more than simpering drawing-room ornaments’ and Swift writing in All Too Well 10m ‘The idea you had of me, who was she? A never-needy, ever-lovely jewel whose shine reflects on you’ ?

And why should women (writers) chose to root for OR criticize these depictions of women’s feelings ? Swift uses both. To me, it’s also a strength to show and not judge that duality of wanting a love so passionate it means self-destruction and understanding that your life, as a woman, goes far beyond love life. And she knew about that from a very young age if you’re thinking about her song Fifteen ‘Back then, I swore I was gonna marry him someday but I realized some bigger dreams of mine’ In the end, this song is less about a failed romantic relationship than self-realization and how important friendship is. A song about teenagers that still speaks to a lot of adult women who know better than to stop liking something because ‘it’s not made for their age’. 😉

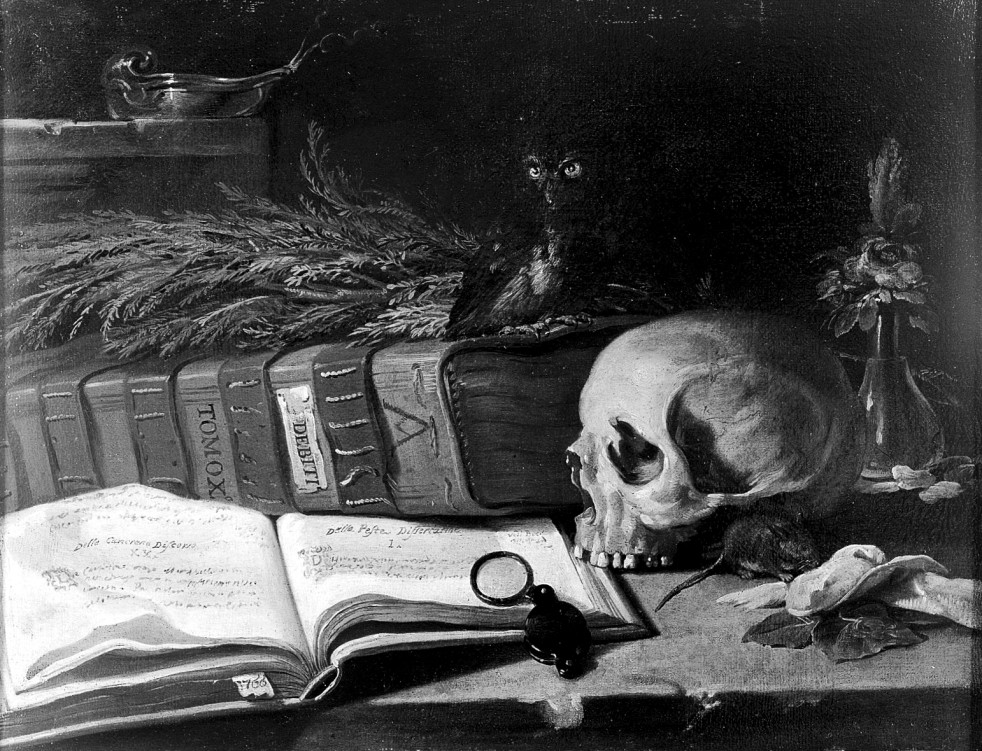

I think it is but a small step from the ‘the yearn for annihilation and selfdestruction in an idolised romantic relationship’ to ‘Eros and Thanatos’ maybe the most universal theme in literature, visual arts and culture as a whole.

And Taylor Swift uses it in some of her lyrics and music, to , in my opinion, an aesthetic perfection. In her case, succes is not coincidence.

Speaking for myself, I find the same perfection of the use of this theme (eros and thanatos) in literature, in the works of Yasunari Kawabata, especially ‘Thousand cranes’ and ‘House of the sleeping beauties’ and for the Dutch literature; Frederik van Eeden ‘Van de koele meren des doods’ en Gerard Reve ‘Het boek van Violet en Dood’.

ps. Interesting comment Juliette.